In the spring of 2019, I obtained tickets for the Brant Foundation’s opening of its new space in East Village NY with an inaugural exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat works. The Peter Brant Foundation is part of this growing number of “private collection museums” by billionaires who are given huge tax breaks for” sharing” with the public their art collections but under limited terms set by the owners (another tax scam favoring the elite). Peter Brant (who by the way has a checkered past) has been a long-time collector and supporter of Jean-Michel’s work.

The opportunity to see over 70 pieces of Basquiat’s artworks, which today mostly is in the hands of private collectors, was indeed a joy. I was glad I had fought hard to get those damn tickets. The combination of a beautifully designed 100-year-old building (formerly a substation for Con Edison) and four floors of Basquiat’s artworks with amazing views of the city urban landscape where Jean-Michel lived and honed his talent was just utterly breathtaking.

Who was Jean-Michel Basquiat ?

This year (2020), Jean-Michel would have turned 60 years old if he had not overdosed on heroin at the age of 27, depressed and lonely. He died at a time when he was beginning to experience some success for his radical approach to modernizing Contemporary Art that for the most part, ignored the Black experience of growing up in a racist America.

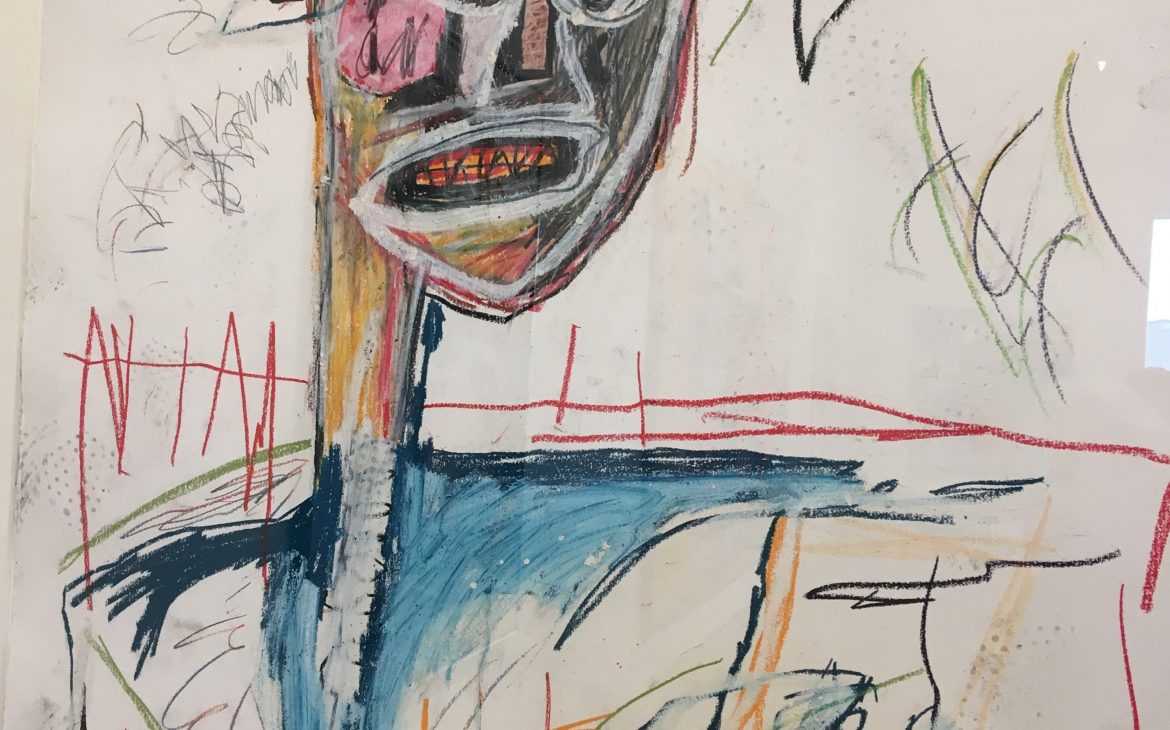

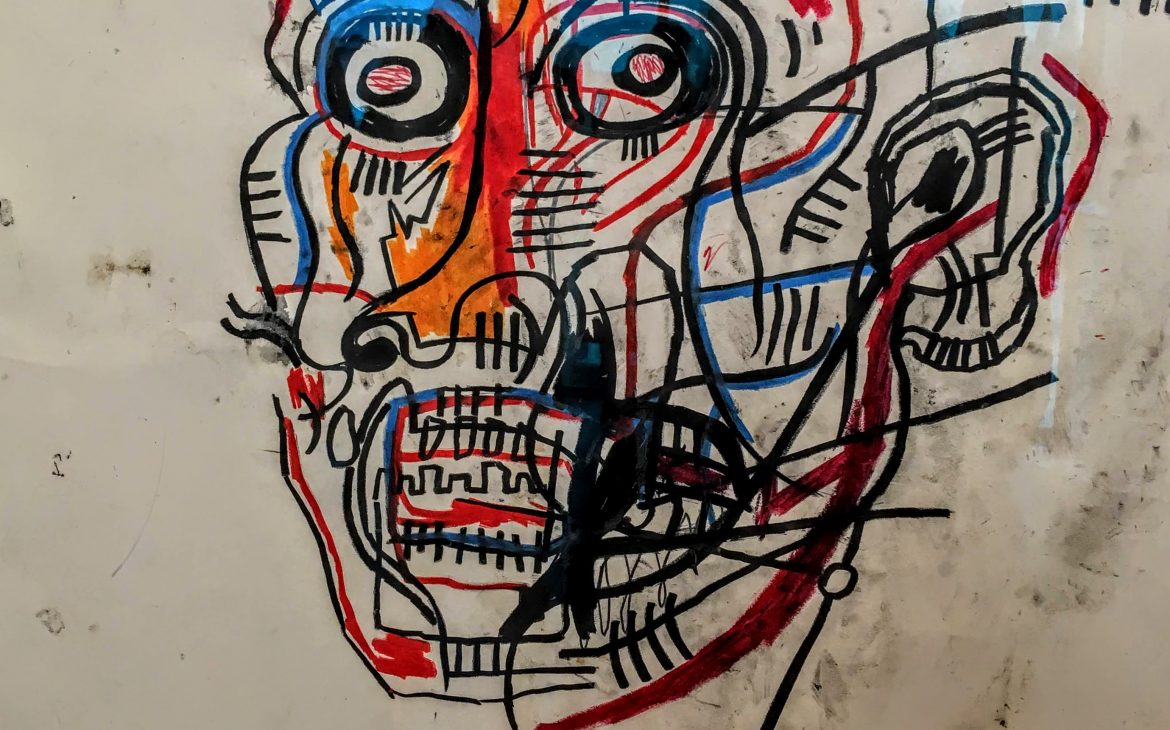

Jean-Michel was born in Brooklyn, NY, to a Puerto Rican mother and a Haitian father. As a young black adolescent, his destiny was marked by two experiences that help shape and cultivate his love and passion for the Arts. The first was a car accident at the age of 7. While hospitalized, his mother gave him a Henry Gray’s Anatomy textbook, that shaped his obsession with the human body and the skull of which so much is reflected in his work. The second was attending an alternative school where visits to museums fueled his exposure to the Art World. There he met Al Diaz, another teenage Puerto Rican, and started SAMO, which led to an evolved form of Graffiti.

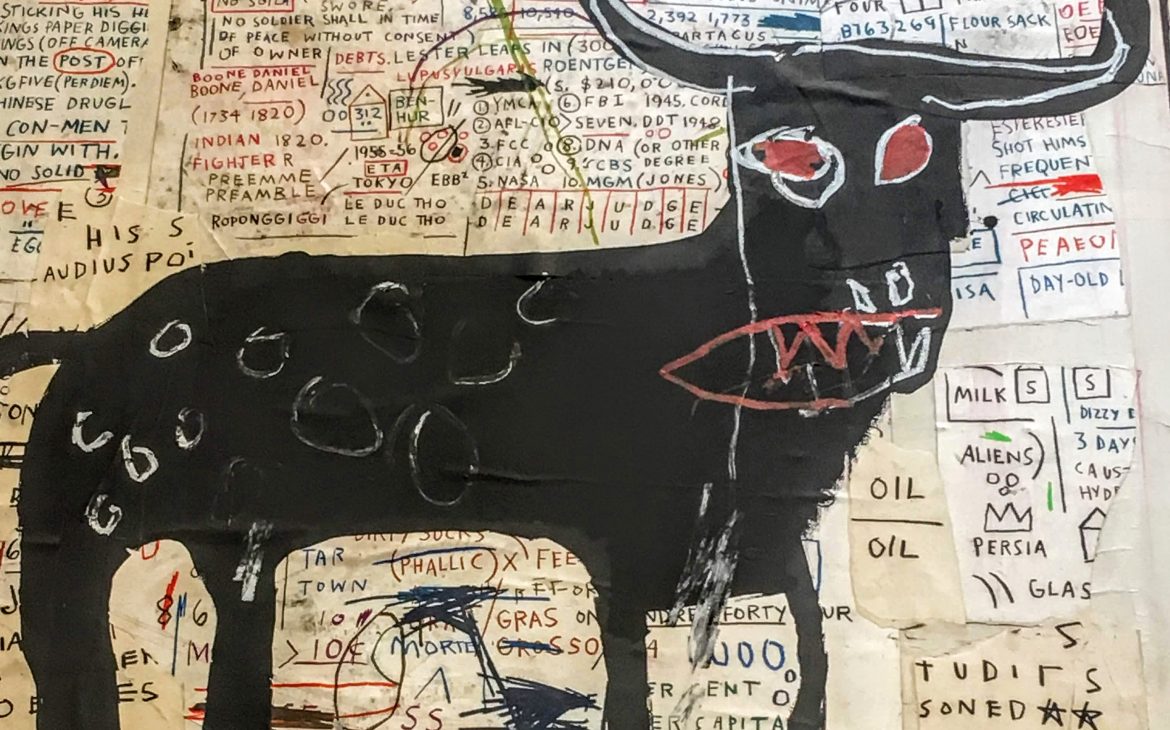

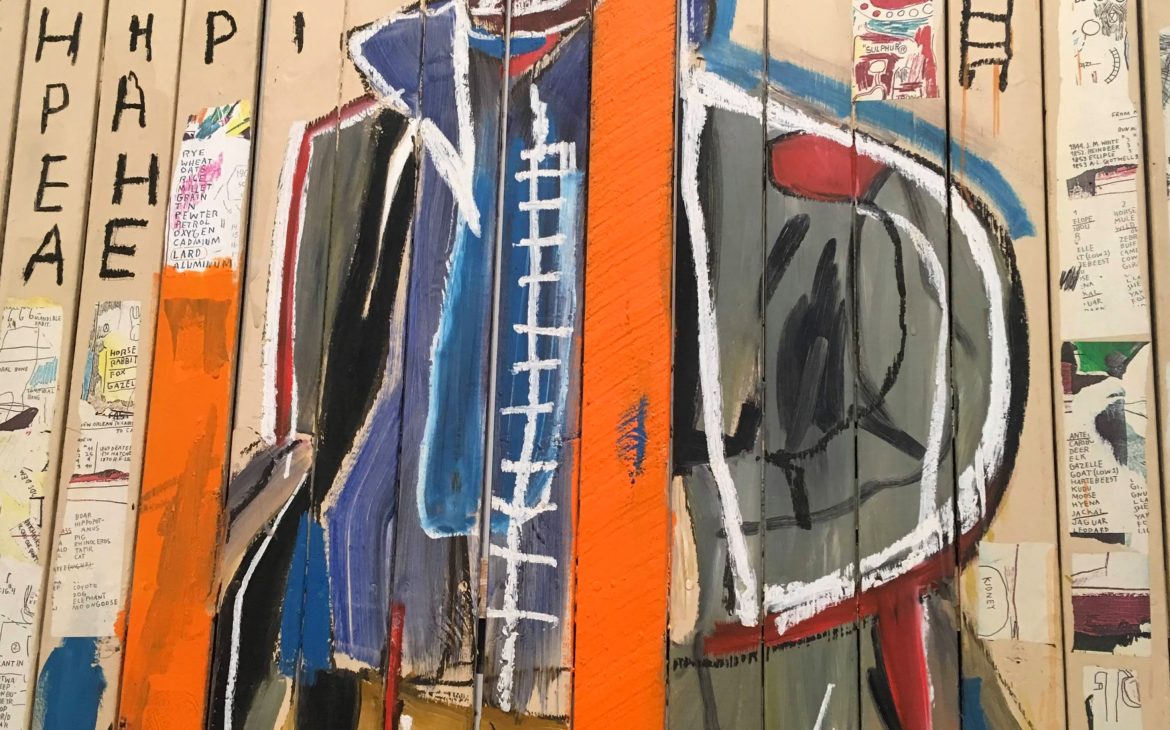

In the late 70s-80s, when Graffiti was taking over the walls and public spaces of New York City, most of it was tagging— a nickname with a number that was significant to teenagers whose only goal was to tag as many places as possible as an expression of their identity. A primitive way of branding among their peers as compared to Instagram today. Both Jean-Michel and Al Diaz elevated Graffiti one step forward by painting or drawing messages instead of just tagging; this gave them notoriety. This eventually became a familiar aspect of Jean-Michel’s artistry using texts, phrases, messages, and symbols such as halos, grids, arrows, and crowns throughout his works.

During his short life, Jean- Michel produced over 1,000 paintings and 2,000 drawings, many in the hands of private collectors since museums were too late to recognize his work and were eventually priced out by the same elites who are their donors. This is unfortunate because it limits public access to his work. The cost to mount an exhibition is extremely expensive and time-consuming that drives the admission price up.

Basquiat’s works are rebellious and reflective of the racism and classism embedded in the Art World and the day-to-day struggle of a poor young black man. When you examine his work, you see references of a knowledgeable person that includes all forms of music, especially hip hop, punk, and rock, as well as poetry. He also references legendary artists such as Leonard Da Vinci, Pablo Picasso, and Jackson Pollock in many of his works.

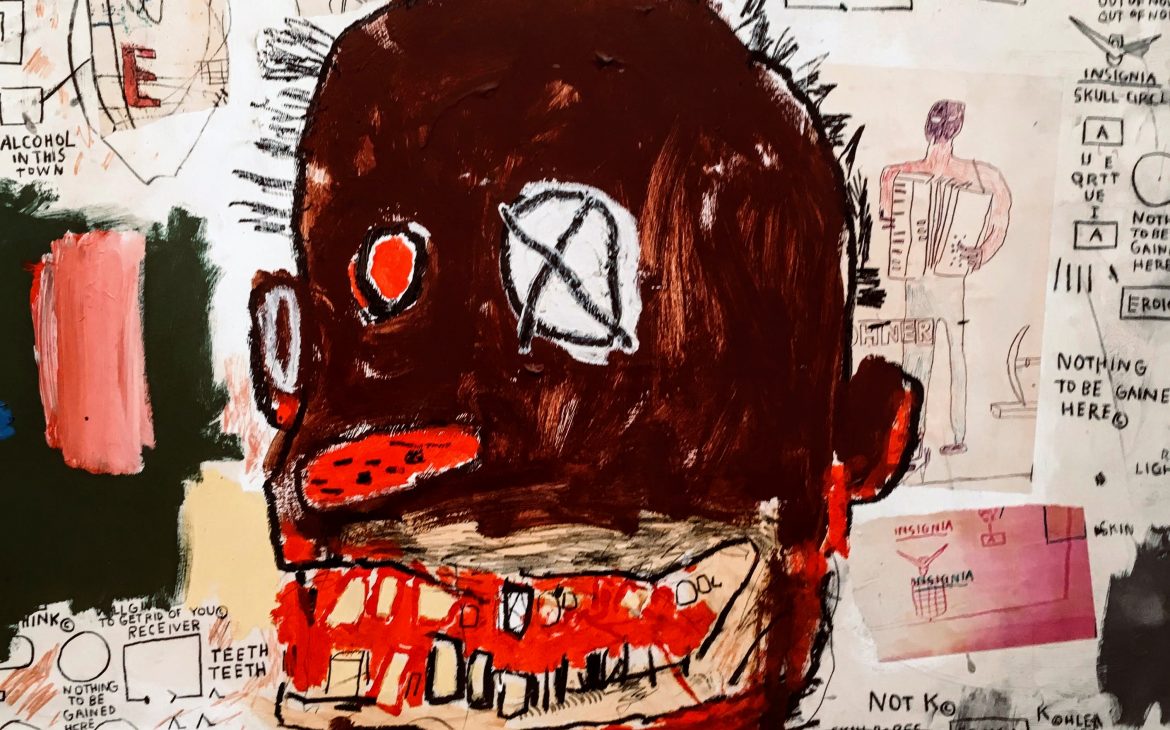

As a black man, Jean Michel celebrated African American athletes and musicians and his African roots while continuously raising his objections to racism, greed, and the exploitation of black communities. He consistently used the symbol of a king’s crown to reference success among his Black heroes and was outspoken about the lack of Blacks in the Art World and the indignities that he experienced as a young black man even as he gained fame and money.

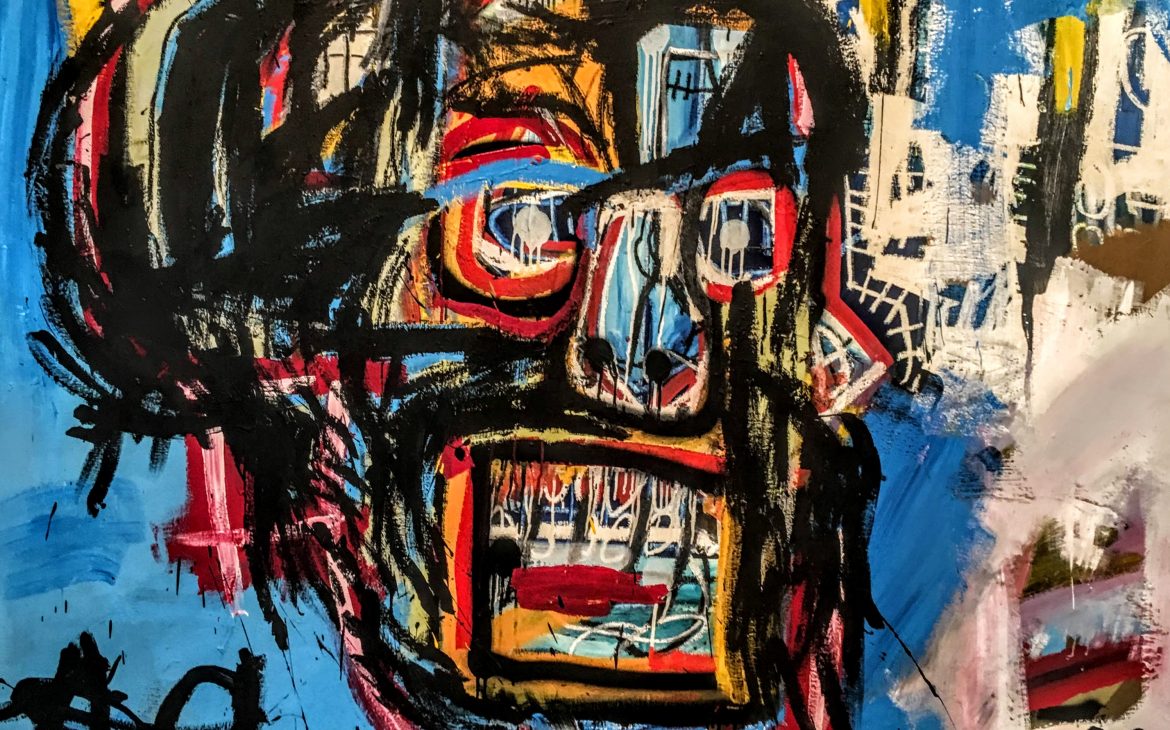

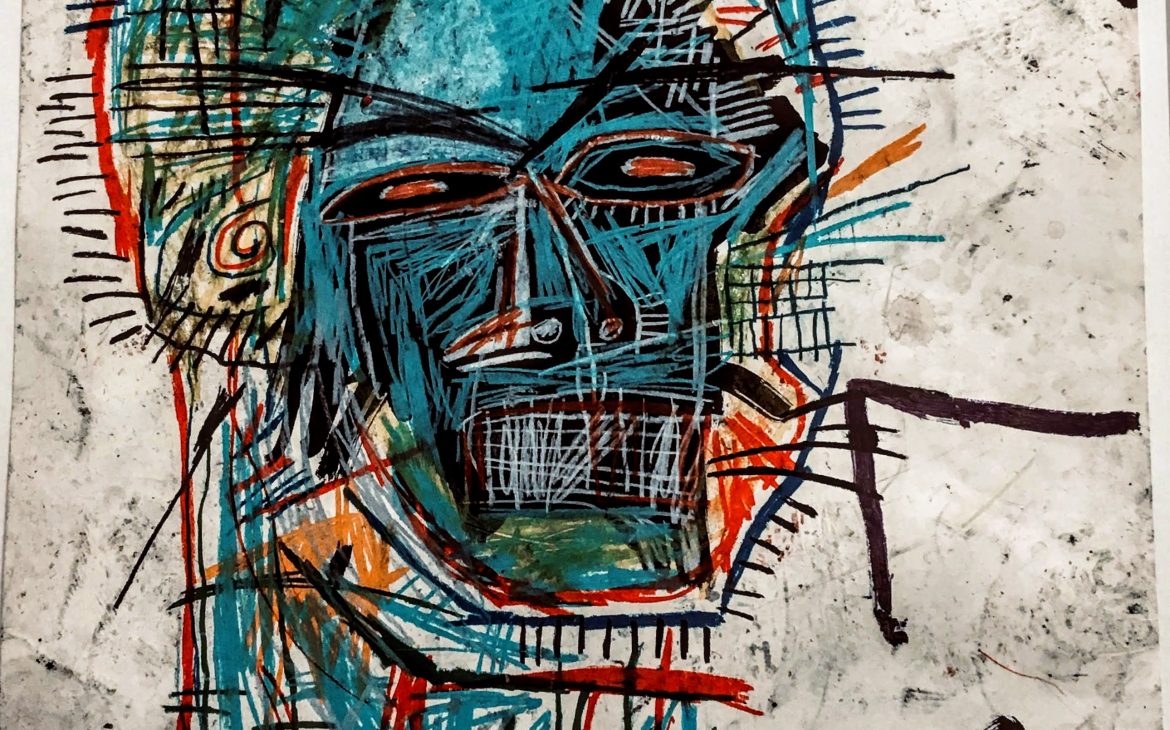

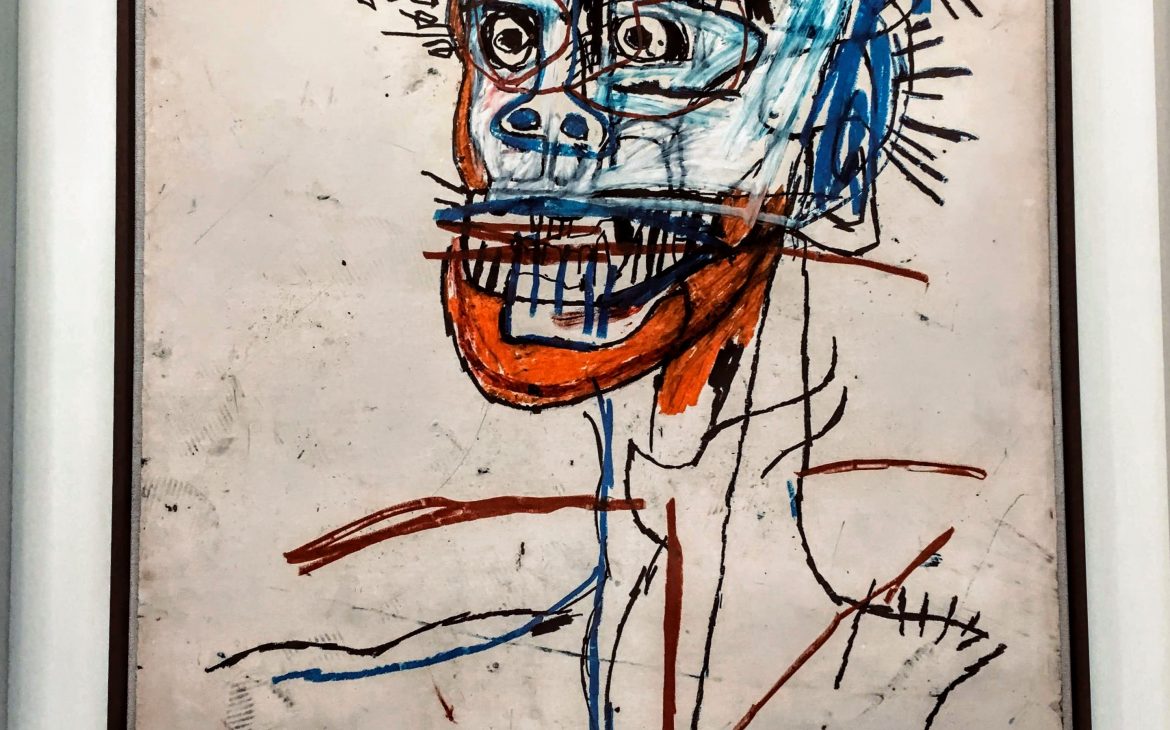

A constant theme in his work consists of parts of the human anatomy, specifically skulls with bulging eyes that are intense and provocative. When observing his work, you can’t help sensing darkness, even expressions of anger, imagery that are haunting yet playful in how he draws and paints his characters. His paintings are intensely vibrant with the color black being a constant theme that clearly speaks to who he is and how he chooses to be identified.

If Jean-Michel were alive today, it would be hard to imagine what the evolution and variations of his body of work would look like? Would he have had the equivalent of a rose or blue period like Picasso who remained creative throughout his aging life, or would have he burned out much like his mentor Andy Warhol and others?

Jean Michel Relevancy to Today Social Justice Movement

No doubt, he left an indelible mark in contemporary art history and is increasingly becoming part of Pop culture, much like Frieda Kahlo, Andy Warhol, and others where their works and image are reflective in all aspects of American life. The only difference is that he brings a life story and a body of work that seeks to raise one’s consciousness of the racial divide and inequities that exist then and today throughout the world. This, I believe, is why there is a growing interest in his life’s work and voice. Unlike so many other visual artists, his message of inequality is even more relevant today as it was for him growing up. He is now an inspiration to so many young black and brown fledgling artists who seek to be creative and be who they are in a world that still marginalizes them as second-class citizens.

Of the 70 pieces shown at the exhibition, I so am happy to share these 30 pieces.

Click the center of the photo to see the full view

“For more stories and photos like these, please click here to subscribe!“

Karen Thomas

Came to Paris in 2018 with an artists pal to see the Basquiat exhibition at the Louis Vitton Foundation there… It was superb and a great space to showcase the breath and depth of his genius… It is unfortunate that it was not realized in his tortured lifetime… Thank you for sharing this tribute Grizel…

LimitedLimitless

Karen, yes truly an amazing artist. I know we have more like him, today, hopefully with a better future. Continue to enjoy Paris

willie logan

I fell as though I just completed an art appreciation class, enlightening, engaging and so true!

LimitedLimitless

Thanks, Willie It’s hard to not appreciate someone like Jean- Michel

Reggie

Piece of writing writing is also a fun, if you know afterward you can write if not it is complex to write.

Also visit my blog – Jerri

Marshall

I am really inspired with your writing skills as smartly as with the layout on your

weblog. Is this a paid subject or did you modify it yourself?

Either way stay up the excellent high quality writing, it’s rare to peer a great

blog like this one nowadays..

my web site – Robert

Akilah

Wow, this piece of writing is pleasant, my younger sister is analyzing such things, thus I am going to let know her.

my site Dee

Clemmie

I have to thank you for the efforts you have put in penning this blog.

I am hoping to see the same high-grade blog posts

by you later on as well. In fact, your creative writing abilities

has inspired me to get my own, personal site now 😉

My web-site Laurie

Dorie

That is a good tip especially to those fresh to the blogosphere.

Short but very precise information… Thanks for sharing this one.

A must read article!

My blog post … film semi layarkaca21

Ladonna

I have to thank you for the efforts you’ve put in penning this

website. I really hope to see the same high-grade blog posts by

you in the future as well. In truth, your creative writing abilities

has encouraged me to get my own site now 😉

Review my web page layarkaca21 indoxx1

Alfredo

I savor, cause I found just what I was having a look for.

You’ve ended my 4 day lengthy hunt! God Bless you man. Have a nice day.

Bye

My webpage – layarkaca21 lk21

Antonietta

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was

searching for!

Feel free to visit my blog Hairoxol Fortem

Mariana

I don’t even know the way I finished up here, but I believed this publish

was once great. I do not understand who you might be however certainly you are going to a well-known blogger in the event you are not already.

Cheers!

my web page … layarkaca21 xxi

Astrid

Saved as a favorite, I love your blog!

My web page :: https://csgrid.org/csg/team_display.php?teamid=373441

Israel

Oh my goodness! Awesome article dude! Many thanks, However I am having problems with

your RSS. I don’t understand the reason why I can’t subscribe

to it. Is there anybody getting the same RSS issues?

Anyone that knows the solution will you kindly respond?

Thanks!!

Take a look at my webpage daftar s128

Antje

I’m not sure where you’re getting your info,

but good topic. I needs to spend some time learning more

or understanding more. Thanks for wonderful info I

was looking for this info for my mission.

My blog post :: https://freebetweb.com

Mervin

I was wondering if you ever thought of changing the layout of

your site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better.

Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or 2 images.

Maybe you could space it out better?

Look at my site :: agen poker pulsa

Rena

Wow, that’s what I was exploring for, what a information! present here at this blog, thanks

admin of this site.

Here is my web-site – https://kungfuchicken.site/

Wyatt

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. I really appreciate your efforts and I

am waiting for your next write ups thank you once again.

Visit my homepage login poker pulsa

Jarrod

I’m gone to tell my little brother, that he should also visit this

blog on regular basis to get updated from latest gossip.

Feel free to surf to my blog: ayamonline.org

Denese

We absolutely love your blog and find almost all of your post’s to be what precisely I’m looking for.

Do you offer guest writers to write content to

suit your needs? I wouldn’t mind publishing a post

or elaborating on some of the subjects you write in relation to

here. Again, awesome weblog!

Also visit my site judi slot online

Ernest

What’s up everybody, here every person is sharing these

kinds of familiarity, so it’s good to read

this blog, and I used to pay a visit this blog everyday.

my site download s128

Nicki

We’re a group of volunteers and opening a new scheme in our

community. Your website offered us with valuable information to work on. You’ve done an impressive

job and our whole community will be thankful to you.

my homepage :: slot pulsa

Kaylene

I have been surfing online greater than 3 hours these days, yet I by no means found any fascinating article

like yours. It is lovely price sufficient for me. In my opinion, if all webmasters and

bloggers made excellent content as you probably did, the web will likely be much more useful than ever before.

Also visit my homepage :: slot deposit pulsa tanpa potongan

Kennith

If some one needs expert view regarding blogging and site-building then i recommend him/her to pay a visit this blog, Keep up

the fastidious job.

Also visit my web page … daftar slot online

Flossie

Hey there, You’ve done an incredible job. I will definitely digg it and personally suggest to my friends.

I’m sure they’ll be benefited from this web site.

Here is my site … poker pulsa

Lorna

Hi! I could have sworn I’ve been to this site before but after browsing

through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I

found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!

Feel free to surf to my webpage … agen slot joker123

Shoshana

You need to take part in a contest for one of the most useful blogs on the web.

I most certainly will recommend this site!

Feel free to surf to my site deposit pulsa tanpa potongan

Sherlyn

I’ll immediately seize your rss feed as I can’t to find your e-mail subscription hyperlink or

newsletter service. Do you have any? Please let me understand so that I could subscribe.

Thanks.

Review my web page: appartamenti Costa Rei

Hester

What’s up, its pleasant post concerning media print, we

all understand media is a great source of data.

my blog post; pulse oximeter review

Dale

Appreciating the timee and effort you put into your website and detailed inflrmation you provide.

It’s great to come across a blog every once in a while

that isn’t thhe same out of date rehashed material. Wonderful read!

I’ve saved your site and I’m including your RSS feedfs

to my Google account.

My web blog; Among us mod apk

Elba

Interesting blog! Is your theme custom made or did you download it

from somewhere? A theme like yours with a few simple adjustements would really make my blog jump out.

Please let me know where you got your theme. Kudos

Also visit my blog affitto appartamento villasimius

Sue

Hmm it appears like your website ate my first comment

(it was extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I had written and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still

new to everything. Do you have any tips and hints for novice blog writers?

I’d really appreciate it.

Feel free to surf to my blog post … call auto parts

dating sites free

dating site,free dating sites

dating site,free dating online http://freedatingste.com/

Klaus

What i do not realize is if truth be told how you are no longer really much more neatly-preferred thasn you may be now.

You’re very intelligent. You realize therefore considerably wuth regards to this matter, produced me personally imagine it from numerous various angles.

Its like women and menn are not involved until it is

onne thing to accomplish with Woman gaga! Your personal stuffs great.

At all times care for it up!

My web site … among us mod ips

Hugo

Article writing is also a excitement, if you be acquainted with afterward you can write if not it is complicated to write.

My page … bong88

Martin

Greetings from Los angeles! I’m bored to tears at work

so I decided to check out your blog on my iphone during lunch break.

I really like the knowledge you present here and can’t wait

to take a look when I get home. I’m shocked at how quick your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, very good blog!

Feel free to visit my web site Darby

Antoinette

Can I simply say what a comfort to discover someone who genuinely knows what they are discussing on the web.

You actually understand how to bring an issue to light and make it important.

More people really need to check this out and understand this side of your story.

I was surprised you aren’t more popular given that you definitely possess the gift.

Feel free to surf to my page; w88

Dyan

I’ll immediately snatch your rss as I can’t in finding your e-mail subscription hyperlink or newsletter service.

Do you’ve any? Please allow me realize in order that I may subscribe.

Thanks.

my site … smartband

Tahlia

Why users still make use of to read news papers when in this technological

world the whole thing is presented on net?

my homepage … cheap flights

Xavier

This is my first time go to see at here and i am really

impressed to read everthing at alone place.

Here is my website cheap flights

Dalene

I do not even know how I ended up here, but I thought this post was good.

I don’t know who you are but certainly you’re going to a

famous blogger if you are not already 😉 Cheers!

Feel free to surf to my site … fb88

Lavonda

With havin so much content do you ever run into any problems

of plagorism or copyright infringement? My website has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it

seems a lot of it is popping it up all over the web without my agreement.

Do you know any ways to help protect against content from being stolen? I’d genuinely

appreciate it.

Also visit my homepage … cheap flights (tinyurl.com)

Twila

Its like you read my mind! You appear to know a lot

about this, like you wrote the book in it or something.

I think that you can do with a few pics to drive the message home a bit, but

other than that, this is wonderful blog.

An excellent read. I’ll definitely be back.

Look at my blog … cheap flights

Rebekah

Spot on with this write-up, I really believe this website needs a lot more attention.

I’ll probably be returning to read through more, thanks for the information!

Also visit my webpage: cheap flights (tinyurl.com)

Johnie

constantly i used to read smaller articles or reviews that as

well clear their motive, and that is also happening with this post which I am reading at this place.

Here is my website: cheap flights (tinyurl.com)

Stan

I’m extremely pleased to find this site. I want tto to thank you for your

time just for this fantastic read!! I definitely really liked every little bit of it and I have

you book-marked to ssee new things in your website.

Feel free to visit my page – among us mod windows

Franziska

When some one searches for his required thing, so he/she

wishes to be available that in detail, therefore that thing is maintained over here.

My web-site … judi slot online

Allie

Thankfulness to my father who told me concerning this web site, this blog is in fact amazing.

Feel free to visit my web page – freebetweb.net

Jessika

I’ll right away seize your rss as I can not to find your email

subscription hyperlink or newsletter service. Do you have

any? Please permit me recognise in order that I may subscribe.

Thanks.

Feel free to surf to my web page … ayam

Clemmie

If you wish for to obtain a great deal from this piece of writing then you have to apply

these techniques to your won blog.

Review my site :: judi pulsa online

Woodrow

bookmarked!!, I like your blog!

Also visit my web page; aduayamfilipina.com

Fidel

I’m truly enjoying the design and layout of your blog.

It’s a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more pleasant for me to come here

and visit more often. Did you hire out a designer to create

your theme? Great work!

Review my web page; s128 apk

Van

Awesome things here. I am very satisfied to peer your

article. Thank you so much and I’m looking ahead to contact you.

Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Also visit my website … joker123 deposit pulsa

Rashad

At this time I am going away to do my breakfast,

afterward having my breakfast coming yet again to read more news.

My site :: poker via pulsa

Genia

Saved as a favorite, I love your web site!

Also visit my site – s128 login

Jocelyn

I couldn’t resist commenting. Very well written!

Stop by my site :: poker online depo pulsa

mshahid

I definitely enjoying every little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you post. vape attic olathe

Isabel

I read this paragraph completely about the difference of newest and previous technologies,

it’s remarkable article.

Check out my site web hosting (http://lexlydia.net/forums/users/louannfossett4)

Rosalind

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to

make your point. You obviously know what youre talking about, why waste your intelligence

on just posting videos to your blog when you could be

giving us something informative to read?

Take a look at my webpage … s128 login

Yetta

Having read this I believed it was very informative.

I appreciate you taking the time and effort to put this article

together. I once again find myself spending a lot of

time both reading and leaving comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

my web page … gamefly

Celinda

Hi just wanted to give you a brief heads up and let you know a few

of the pictures aren’t loading correctly. I’m not sure why but

I think its a linking issue. I’ve tried it in two different internet browsers and both show the same outcome.

my website; slot deposit pulsa tanpa potongan bonus awal 100

Hortense

For most recent information you have to pay a visit the web and on web I found this web page as a best web page for latest updates.

games ps4 185413490784 games ps4

my webpage – coconut oil

Harriett

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article author

for your blog. You have some really good articles and I think I would be a good asset.

If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some

content for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine.

Please shoot me an e-mail if interested. Cheers!

Feel free to visit my blog post: ps4 games (http://tinyurl.com)

Mallory

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before

but after browsing through many of the posts I realized it’s new to me.

Anyhow, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back often!

Here is my web page: ps4 games, tinyurl.com,

Anitra

Hi, I do believe this is an excellent website. I stumbledupon it 😉 I may come back once

again since I saved as a favorite it. Money and freedom is the best way

to change, may you be rich and continue to help other people.

Here is my site – web hosting (bit.ly)